The Pandemic Paradox

We’ve all seen countless articles detailing how COVID-19 has fundamentally changed the workplace and the workforce – possibly forever. Many of the changes wreaked on the workforce will deliver a positive change to employee wellness (both mental and physical) and will likely deliver significant productivity gains for many businesses.

COVID-19 has also delivered one of the biggest looming workforce challenges of our time – a global labour shortage, though I contend that the depth and scale of the looming global labour shortage has been self-inflicted by government.

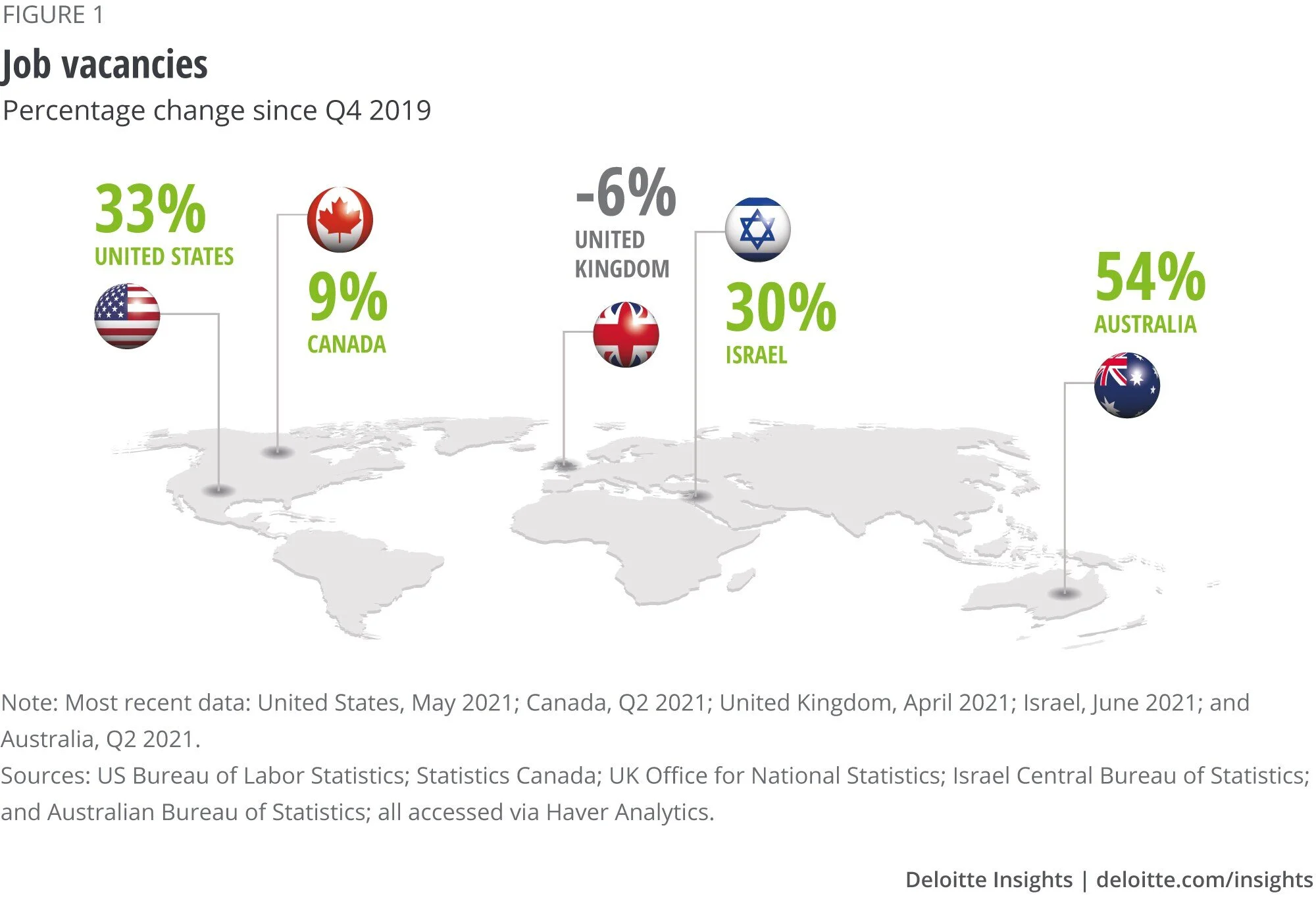

This evolving global economic environment has created what I call the pandemic paradox – numerous developed economies are seeing continued high unemployment levels in 2021, at the same time as seeing historically high job vacancies across multiple industry sectors.

What does this apparent workforce contradiction mean for global businesses preparing to re-engage with the global marketplace as international borders start to re-open?

Massive government spending has underwritten many businesses during periods of extended lockdown. This has kept unemployment lower than may otherwise have been the case, but the sheer scale of government stimulus has created a global talent vacuum.

For over two decades, the business community has relied on the use of skilled foreign talent to drive growth and innovation, particularly in middle economies such as Australia, Singapore and Canada.

COVID-19 suddenly turned the global talent tap off, which has not been replaced by talent returning to their home country during international border closures.

At the same time, extended lockdowns have driven high unemployment, with some industries particularly impacted.

This phenomenon has created a challenging dilemma for both government and the business community. Many developed economies are observing worker shortages coincide with elevated unemployment rates. This scenario is being exacerbated by the shift in workforce and workplace priorities by talent.

The policy shift driving the attraction and retention of talent requires a rethink of business operating models which support cross-border movement.

The pandemic has changed the future of work

At a time of unprecedented disruption in the global economy, we are witnessing in real-time the largest movement of talent in our working lifetimes.

The business world is trying to interpret the longer-term impacts on the workforce and workplace wreaked by COVID-19.

Extended periods of disruption to existing workplace arrangements, including working from home for many months, has enabled talent to assess their priorities for the future. If business leaders are slow to respond to the evolving needs of their workforce, talent will explore their options in a market which provides them with more employment options than was the case in the pre-pandemic world.

The employee experience has become the new currency of global talent. This phenomenon has increased the focus on and importance of how immigration and wider cross-border talent strategies attract, retain and incentivize skilled labor.

The COVID-19 pandemic has effectively acted as a reset of the global workforce. This has been most particularly felt in businesses which deploy labor globally, which will be critical to help economies decimated by COVID-19 lockdowns recover.

Key to driving economic growth is the ability for developed economies to attract talent – particularly skills which are in high demand arising from the impact of COVID-19 such as medical and information technology professionals, as well as business executive roles.

However, the pendulum has shifted significantly from employers in favor of skilled talent in shaping the workplace and workforce that they would like to participate in.

Factors such as the explosion of interest in remote work and work-from-anywhere, the increased use of technology for talent to deliver outcomes, and importantly an increased focus of global talent on workplace wellness has contributed to large scale migration of talent, where skilled labor look to negotiate workplace arrangements aligned to their changed priorities.

The international movement of talent needs to kick start the global economy

The sudden halt to the global movement of talent in early 2020 has significantly contributed to labour market shortages. The United Kingdom suffered a double blow to access to global talent as a result of BREXIT which caused many European Union workers the right to work in the UK.

According to one informed source, approximately 1.3 million non-UK workers left the United Kingdom as a result of BREXIT, which equates to approximately 4% of the workforce. This loss of labour was exacerbated in some industries such as accommodation and food service, which are now re-opening following a successful COVID vaccine roll-out.

Other countries which have long relied on the use of skilled foreign talent to grow their economy such as Canada, Singapore and Australia, have experienced similar talent shortages during the pandemic. In the case of Australia, the population fell for the first time in a century last year as border closures starved the country of much needed migrants.

These middle economies will find restarting their local economies very challenging as a result of the changing face of the global talent workforce. This is likely to deliver some innovative government thinking to attract skilled foreign labour, and in some cases changes to regulatory frameworks (taxation and legal) to incentivise skilled talent in short supply to remain.